20 Frank Lloyd Wright Houses That Changed America

Frank Lloyd Wright revolutionized American architecture with his innovative designs that harmonized with nature.

His philosophy of ‘organic architecture’ created homes that felt like natural extensions of their surroundings rather than imposing structures.

These 20 remarkable houses showcase Wright’s genius and continue to influence architects and homeowners more than half a century after his death.

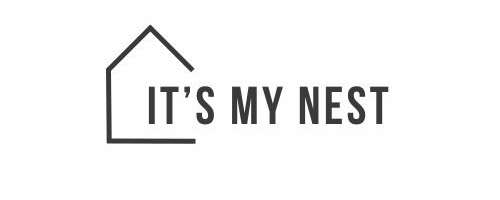

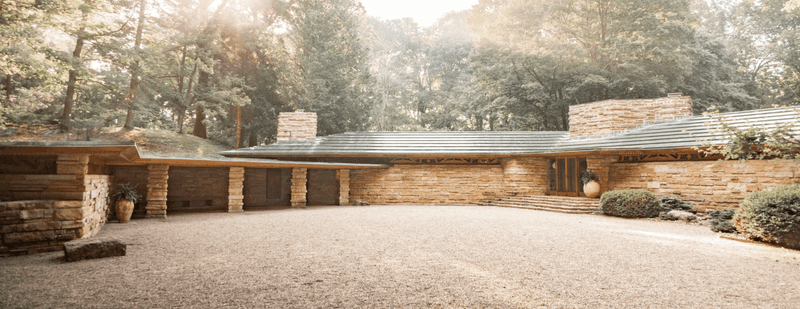

1. Fallingwater (Mill Run, Pennsylvania)

Perched dramatically over a waterfall, this iconic home redefines the relationship between architecture and nature. Built in 1935 for the Kaufmann family, Fallingwater’s cantilevered terraces seem to float above Bear Run stream.

The integration of natural elements—local sandstone walls matching the surrounding rocks and expansive windows framing forest views—creates a living space that feels like part of the landscape itself. Today, it remains Wright’s most celebrated masterpiece.

2. Robie House (Chicago, Illinois)

With its striking horizontal profile, the Robie House epitomizes Wright’s Prairie School style. Completed in 1910, its low-slung roof and dramatic overhangs create a sense of shelter while emphasizing the flat Midwestern landscape.

Inside, an open floor plan and ribbon windows revolutionized domestic living. The home’s innovative use of space influenced countless suburban houses across America. Art glass windows with geometric patterns filter light, creating ever-changing interior atmospheres throughout the day.

3. Taliesin (Spring Green, Wisconsin)

Rising from personal tragedy, Wright built this rural estate after scandal forced him from Chicago. Named with the Welsh word for “shining brow,” Taliesin sits halfway up a hill rather than atop it—exemplifying Wright’s belief in working with, not against, nature.

Serving as both home and studio, the complex evolved over decades as Wright’s living laboratory. Despite suffering two devastating fires, the restored property showcases his genius for integrating buildings with their surroundings through local materials and panoramic views of the Wisconsin River valley.

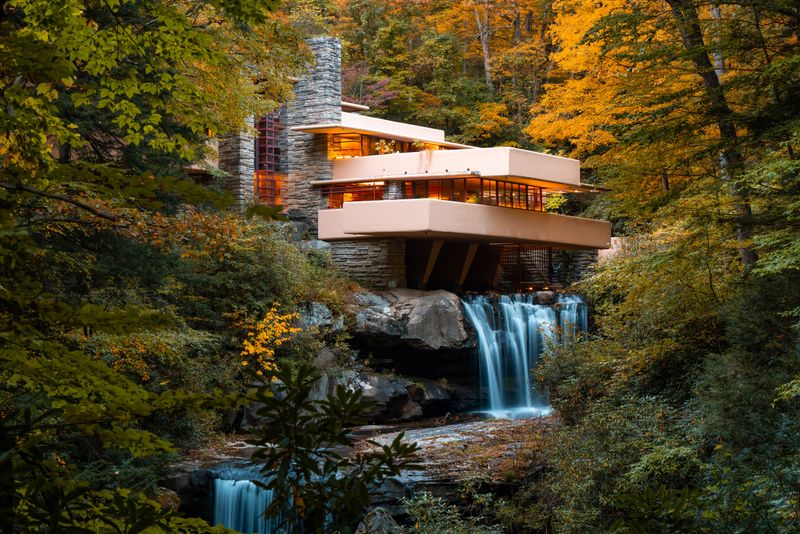

4. Taliesin West (Scottsdale, Arizona)

Amid the Sonoran Desert’s harsh beauty, Wright created his winter home and architectural school. Beginning in 1937, this striking complex emerged from desert materials—local rocks embedded in concrete walls and canvas roof panels that filtered the intense Arizona sunlight.

Unlike conventional buildings that shut out the desert, Taliesin West embraces its environment. The low-slung structures seem to grow from the earth, while dramatic angles echo nearby mountain peaks. Still functioning as an architectural school today, it stands as Wright’s desert laboratory.

5. Hollyhock House (Los Angeles, California)

Commissioned by oil heiress Aline Barnsdall, this 1921 masterpiece marked Wright’s first Los Angeles project. Taking inspiration from pre-Columbian temples, the home features massive concrete walls and a central courtyard that creates a fortress-like sanctuary from urban bustle.

Throughout the design, stylized hollyhock flower motifs—Barnsdall’s favorite—appear in concrete details, furniture, and art glass. The home’s innovative indoor-outdoor connections through pergolas and terraces perfectly suited California’s climate, influencing countless Southern California homes that followed.

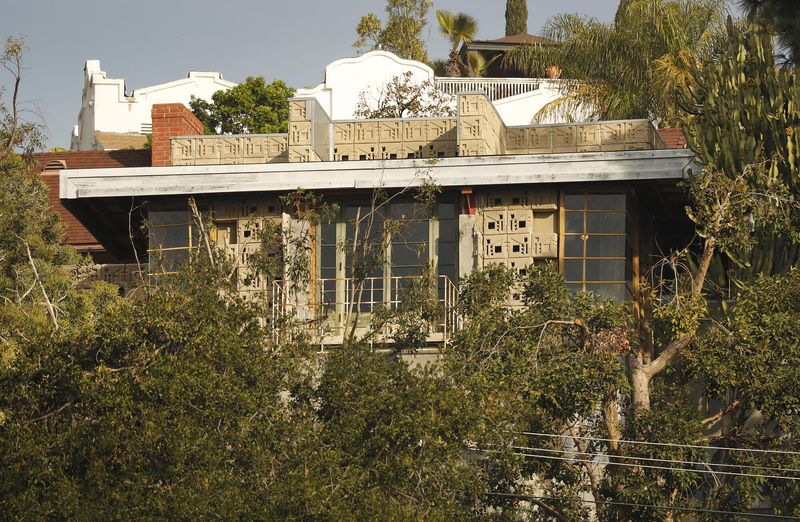

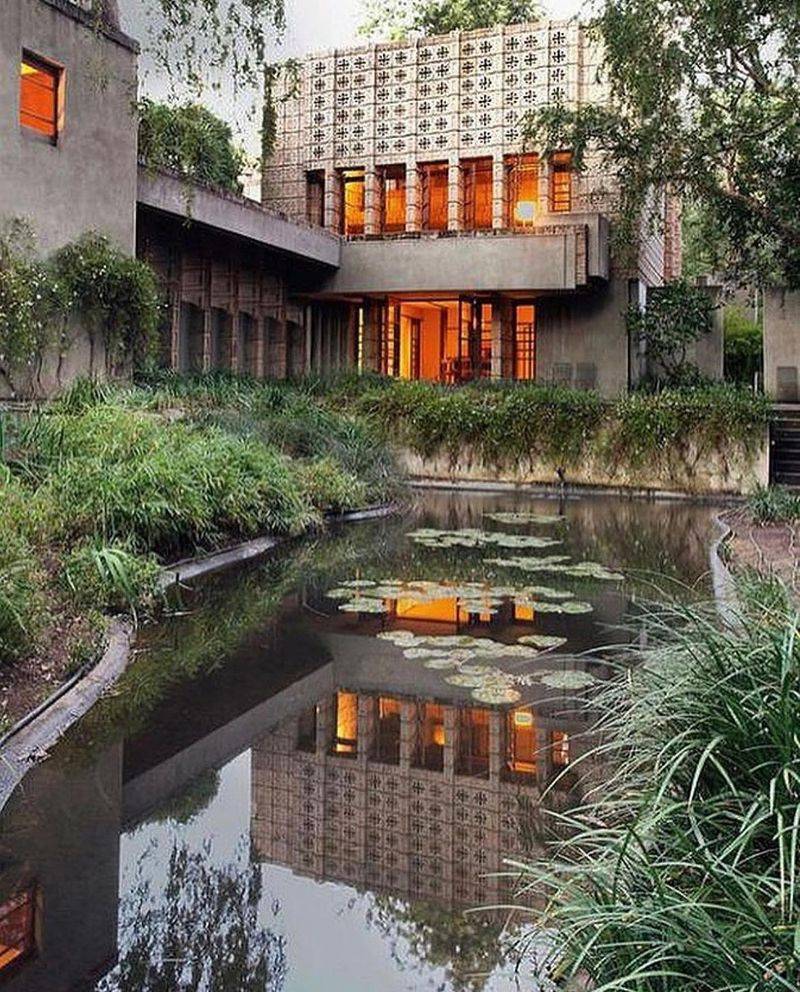

6. Ennis House (Los Angeles, California)

Looming above Los Feliz like an ancient Mayan temple, the Ennis House has become a Hollywood icon. Constructed in 1924 using textile blocks—concrete blocks with intricate geometric patterns—it creates a stunning visual effect of light and shadow across its imposing façade.

Movie buffs might recognize it from films like Blade Runner and House on Haunted Hill. Despite earthquake damage and years of neglect, a $17 million restoration has returned this architectural marvel to its former glory, preserving Wright’s most dramatic textile block creation.

7. Storer House (Hollywood Hills, California)

Hidden in the Hollywood Hills, this compact gem showcases Wright’s textile block construction method. Built in 1923 for Dr. John Storer, the home’s patterned concrete blocks create both structure and decoration—a revolutionary concept that eliminated the need for separate ornamental elements.

Film producer Joel Silver later purchased and meticulously restored the property with Wright’s grandson, architect Eric Lloyd Wright. Its terraced gardens and geometric blocks harmonize with the hillside setting. Though smaller than other Wright homes, it demonstrates his ability to create drama in modest spaces.

8. Freeman House (Los Angeles, California)

Clinging to a steep Hollywood hillside, this 1924 textile block house demonstrates Wright’s ability to conquer challenging terrain. Built for Samuel and Harriet Freeman, the home features two compact stories with an open living area that maximizes panoramic Los Angeles views.

The perforated concrete blocks create dappled interior light while providing natural ventilation, an elegant solution to California’s climate before air conditioning.

9. Millard House (La Miniatura) (Pasadena, California)

Nestled in an arroyo, this 1923 creation pioneered Wright’s textile block system. The architect described it as “the cheapest house I could build,” yet its innovative construction method produced extraordinary beauty through simple materials.

Water features and reflecting pools surround the home, creating a serene microclimate. Despite initial skepticism about concrete’s aesthetic potential, La Miniatura proved that industrial materials could create spaces of remarkable warmth and intimacy.

10. Pope-Leighey House (Alexandria, Virginia)

Affordable beauty defines this modest Usonian home originally built in 1941 for journalist Loren Pope. When threatened by highway construction in 1965, the entire structure was carefully moved to preserve Wright’s vision of democratic architecture for middle-class Americans.

Clever space-saving features abound: built-in furniture, clerestory windows that eliminate the need for curtains, and passive heating and cooling systems. At just 1,200 square feet, the home demonstrates Wright’s genius for making small spaces feel expansive through open planning and connection to outdoor gardens.

11. Jacobs House (Usonian #1) (Madison, Wisconsin)

Revolutionary in its simplicity, this 1937 home launched Wright’s Usonian concept—affordable yet beautiful houses for middle-class Americans. Built for just $5,500 (about $100,000 today), it rejected basements, attics, and decorative trim in favor of an L-shaped plan organized around a garden.

Radiant floor heating—then virtually unknown in American homes—eliminated unsightly radiators. The carport (a term Wright invented) replaced the traditional garage. These innovations influenced thousands of mid-century homes across America, democratizing good design for everyday families.

12. Zimmerman House (Manchester, New Hampshire)

Tucked away in a quiet neighborhood, this complete Usonian package includes Wright-designed furniture, textiles, and even garden plantings. Completed in 1952 for Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman, the home remains exactly as the couple lived in it for decades.

The Zimmermans were so delighted with Wright’s creation that they never changed a thing—even leaving their original Wright-selected dishware to the museum that now operates the property.

13. Darwin D. Martin House (Buffalo, New York)

Spanning a full city block, this ambitious complex represents Wright’s Prairie style at its most elaborate. Commissioned by businessman Darwin Martin in 1905, it includes the main house, a smaller home for Martin’s sister, a gardener’s cottage, and connecting pergolas.

Nearly 400 art glass windows—including the famous “Tree of Life” design—create kaleidoscopic interior light effects. After decades of neglect, a $50 million restoration has returned the property to its original glory.

14. Avery Coonley House (Riverside, Illinois)

Childhood wonder infuses this 1908 suburban estate designed for a wealthy Chicago couple. Playful elements appear throughout—most notably in the nursery’s art glass windows featuring balloons, confetti, and American flags that create rainbow patterns when sunlight streams through.

Multiple wings embrace outdoor courtyards rather than turning inward. Its influence extends beyond architecture—the geometric window patterns inspired countless decorative designs in furniture and textiles throughout the 20th century.

15. George Blossom House (Chicago, Illinois)

Standing among conventional Victorian homes in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood, this 1892 creation reveals Wright’s early experimentation before developing his mature style. The striking geometric façade hints at his emerging break from traditional architecture.

Unlike his later open-concept designs, the interior follows a more conventional room arrangement. Yet innovative touches appear throughout—Roman brick patterns, built-in cabinetry, and dramatic ceiling heights.

16. Thomas P. Hardy House (Racine, Wisconsin)

Gravity-defying drama characterizes this 1905 home perched on a bluff overlooking Lake Michigan. Unlike most lakefront properties that spread horizontally, the Hardy House rises vertically from its narrow lot, resembling the prow of a ship facing the water.

Living spaces begin on the second floor to maximize lake views. A third-floor balcony cantilevers dramatically over the hillside. Despite its compact footprint, the home feels spacious thanks to Wright’s clever use of double-height spaces and walls of windows framing the spectacular lake panorama.

17. E. E. Boynton House (Rochester, New York)

Nestled among traditional homes in Rochester’s East Avenue Historic District, this 1908 Prairie masterpiece brought Midwestern innovation to upstate New York. Long bands of art glass windows—over 90 in total—create a dazzling play of filtered light throughout the interior.

Unlike many Wright homes that have been museums for decades, the Boynton House has remained a private residence. Recent owners undertook a meticulous two-year restoration, uncovering original details hidden by previous renovations.

18. Willits House (Highland Park, Illinois)

Architectural historians consider this 1901 masterpiece the first fully mature example of Wright’s Prairie style. Its cruciform plan organizes living spaces around a central fireplace—a layout that would influence American homes for generations.

Revolutionary for its time, the home abandons Victorian compartmentalization in favor of flowing spaces. Over 100 art glass windows and skylights create ever-changing patterns of colored light throughout the day.

19. Isaac M. Hagan House (Kentuck Knob) (Chalk Hill, Pennsylvania)

Tucked just seven miles from Fallingwater, this hidden gem demonstrates Wright’s late-career mastery. Built in 1956 when the architect was 86 years old, Kentuck Knob shows his Usonian principles refined to their essence.

Hexagonal geometry organizes the entire design—from the overall floor plan to kitchen cabinet details. Wright never visited the completed house, designing it entirely from topographical maps and one site visit.

20. Arthur Heurtley House (Oak Park, Illinois)

Massive and fortress-like, this 1902 home marks Wright’s decisive break from Victorian traditions. The imposing Roman brick façade with minimal windows creates a sense of mystery from the street, while the rear opens dramatically to a private garden.

Inside, Wright employed one of his favorite devices—a compressed, dark entry sequence that suddenly opens into light-filled living spaces. This theatrical progression creates a powerful emotional impact.